- Home |

- Why With Us |

- About Us |

- Booking |

- Contact Us |

- Site Map

Places of Interest in Bhutan

Bumthang Dzongkhag

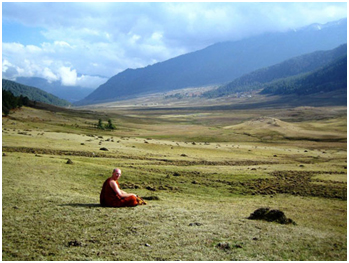

The Bumthang region encompasses four major valleys: Chokhor, Tang, Ura and Chhume. Because the dzongs and the most important temples are in the large Chokhor valley, it is commonly referred to as the Bumthang valley.

There are two versions of the origin of the name Bumthang. The valley is supposed to be shaped like a bumpa, the vessel of holy water that is usually found on the altar of a lhakhang. Thang means ‘field’ or ‘flat place’. The less respectful translation relates to the particularly beautiful women who live here – bum means 'girl'.

Central Bhutan

There is a great variety of people, architecture and scenery in central Bhutan. Because it takes a little extra time to get here, the countryside and hotels see fewer tourists than in Thimphu, Paro and Punakha. In fact, until the 1970s the only way to reach this part of Bhutan was on foot or atop a sure-footed horse.

Across the 3420m-high Pele La and the Black Mountains is the large, fertile Mangde Chhu valley and the great Trongsa Dzong. Commanding the junction of three major roads, Trongsa has long been the glue that holds the country together. Even today the Crown Prince must serve as the penlop (regional governor) of the dzong before he can rule as king.

A short drive over the mountains from Trongsa leads to the four valleys of Bumthang, a magical region of saints and treasure-seekers, great demon-subduing struggles and fabulous miracles, rich with relics from the visits of Guru Rinpoche and Pema Lingma. This forested landscape is Bhutan’s cultural heartland. For the visitor it offers several of Bhutan’s best and oldest monasteries, some great day hikes and short treks and spectacular festivals, primarily at Jampey Lhakhang and nearby Ura. Bumthang is one of the real highlights of Bhutan.

In the south the Royal Manas National Park protects a region of tropical vegetation and rich biodiversity. It’s hoped that the park will soon reopen to foreigners. Central Bhutan is believed to be the first part of Bhutan to have been inhabited, with evidence of prehistoric settlements in the Ura valley of Bumthang and the southern region of Khyeng. These and many other valleys were separate principalities ruled by independent kings. One of the most important of these kings was the 8th-century Indian Sindhu Raja of Bumthang, who was eventually converted to Buddhism by Guru Rinpoche. Bumthang continued to be a separate kingdom, ruled from Jakar, until the time of Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal in the 17th century.

Central Bhutan is believed to be the first part of Bhutan to have been inhabited, with evidence of prehistoric settlements in the Ura valley of Bumthang and the southern region of Khyeng. These and many other valleys were separate principalities ruled by independent kings. One of the most important of these kings was the 8th-century Indian Sindhu Raja of Bumthang, who was eventually converted to Buddhism by Guru Rinpoche. Bumthang continued to be a separate kingdom, ruled from Jakar, until the time of Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal in the 17th century.

During the rule of the first desi (secular ruler), Tenzin Drugyey, all of eastern Bhutan came under the control of the Drukpa government in Punakha. Chhogyel Mingyur Tenpa unified central and eastern Bhutan into eight provinces known as Shachho Khorlo Tsegay. He was then promoted to Trongsa penlop (governor).

Because of Trongsa Dzong’s strategic position, the penlop exerted great influence over the entire country. It was from Trongsa that Jigme Namgyal, father of the first king, rose to power.

Bumthang retained its political importance during the rule of the first and second kings, both of whom had their principal residence at Wangdichholing Palace in Jakar. Several impressive royal residences and country estates remain in the region, including at Kuenga Rabten, Eundu Chholing and Urgyen Chholing.

Chhukha Dzongkhag For travellers Chhukha district effectively consists of the winding road that drops from the mountains through the lush tropical foothills of southern Bhutan to Phuentsholing, the primary land crossing into India. There’s little reason to take this route unless you are headed to or from India, but it’s a dramatic ride and gives you a sense of geographical continuity that flying into Paro doesn’t. En route you’ll pass gigantic ‘Lost World’ ferns that spill into the road and dozens of silver-threaded waterfalls, cascading off high cliffs into the mist.

For travellers Chhukha district effectively consists of the winding road that drops from the mountains through the lush tropical foothills of southern Bhutan to Phuentsholing, the primary land crossing into India. There’s little reason to take this route unless you are headed to or from India, but it’s a dramatic ride and gives you a sense of geographical continuity that flying into Paro doesn’t. En route you’ll pass gigantic ‘Lost World’ ferns that spill into the road and dozens of silver-threaded waterfalls, cascading off high cliffs into the mist.

Along this winding and dangerous 1½-lane highway you may want to point out to your driver the superbly cheesy Indian signboards that remind travellers, for example, that ‘Speed is the knife that kills life’, ‘Speed thrills but kills’, and ‘Impatient on Road, patient of Hospital’. You can’t say you haven’t been warned.

Eastern Bhutan

Even though it is the most densely populated region, eastern Bhutan remains the kingdom’s hinterland. Roads reach the major towns, but most settlements are hidden in the steep hillsides of remote and isolated valleys, some of which are home to minority ethnic groups comprising less than 1000 people.

The dominant language here is Sharchop (language of the east), although there are many local languages and dialects. Sharchop is different enough from Dzongkha that people from eastern and western Bhutan usually have to use English or Nepali to communicate. If you visit a particularly remote village your guide may have to resort to sign language.

The dominant language here is Sharchop (language of the east), although there are many local languages and dialects. Sharchop is different enough from Dzongkha that people from eastern and western Bhutan usually have to use English or Nepali to communicate. If you visit a particularly remote village your guide may have to resort to sign language.

Eastern Bhutanese love their home-brewed arra (rice wine) and locally grown green chillies. Because of the slash-and-burn system of shifting cultivation called tseri, the forest cover at lower elevations is less extensive than in other parts of Bhutan. The lower altitudes mean that spring and summer here are hot, humid and sweaty.

The general quality of hotels, food and service in eastern Bhutan is lower than it is in Thimphu and Paro. Don’t venture into this part of the kingdom unless you have a sense of humour and are able to take a possible lack of hot water and Western toilets in your stride.

It’s a looong drive out to the far east. The good news for tourists is that the border crossing at Samdrup Jongkhar is once again open to foreigners (though for exit only), so you can avoid the winding three-day drive back to Thimphu, with Guwahati and direct flights to Bangkok just a two-hour drive away.

Jakar Near the foot of the Chokhor valley, Jakar (or Chakkar) is the major trading centre of the region. This will probably be your base for several days as you visit the surrounding valleys.

Near the foot of the Chokhor valley, Jakar (or Chakkar) is the major trading centre of the region. This will probably be your base for several days as you visit the surrounding valleys.

Jakar itself is a fairly interesting one-street town, with a goldsmith, tailor, several butchers and a hardware store, and it’s worth a quick wander. As with other towns in Bhutan, Jakar plans to shift location to a new town, just north of the Sey Lhakhang, though no date has been given as yet for the move.

Bumthang has some important festivals, of which the most important is the Jampey Lhakhang Drup, in the ninth month (October). The recently introduced three-day Bumthang tsechu, a week earlier, features mask dancing in the dzong. Tamshing, Nyang and Ura monasteries all have large festivals.

There is a strong wind from the south every afternoon, which makes Jakar nippy in the evenings.

Jigme Dorji National Park

Jigme Dorji National Park is the largest protected area in the country, encompassing an area of 4329 sq km. It protects the western parts of Paro, Thimphu and Punakha Dzongkhags (districts) and almost the entire area of Gasa Dzongkhag. Habitats in the park range from subtropical areas at 1400m to alpine heights at 7000m. The park management has to cope with the needs of both lowland farmers and seminomadic yak herders, and three of the country’s major trekking routes pass through the park. Villagers are also allowed to harvest a wide variety of indigenous plants for use in incense and traditional medicines.

The park is the habitat of several endangered species, including the takin, snow leopard, blue sheep, tiger, musk deer, red panda, Himalayan black bear and serow. Other mammals to be found are leopards, wild dogs, sambars, barking deer, gorals, marmots and pikas. More than 300 species of birds have been catalogued within the park.

Lhuentse There is little to see in Lhuentse and there’s no actual village here, but the dzong is one of the most picturesque in Bhutan. The series of concrete terraces you see as you enter the town, just above the current collection of wooden shops and bars, is the site for yet another of Bhutan’s new towns. The pillared pavilion nearby is a cremation ground.

There is little to see in Lhuentse and there’s no actual village here, but the dzong is one of the most picturesque in Bhutan. The series of concrete terraces you see as you enter the town, just above the current collection of wooden shops and bars, is the site for yet another of Bhutan’s new towns. The pillared pavilion nearby is a cremation ground.

The road terminates in front of the dzong. Adjoining the parking lot are quarters for government officials working in Lhuentse who have been posted to this remote area where housing is scarce.

It’s worth driving up to the Royal Guest House for views of the dzong and the snow peaks at the head of the Kuri Chhu valley. The peak at the head of the valley to the northwest of the guesthouse is Sheri Nyung.

As you leave Lhuentse for Mongar, look out for the ancient ruined bridge down in the valley below, just before the bend in the river.

Lhuentse Dzongkhag

Formerly known as Kurtoe, the isolated district of Lhuentse is the ancestral home of Bhutan’s royal family. Although geographically in the east, it was culturally identified with central Bhutan, and the high route over Rodang La was a major trade route until the road to Mongar was completed. Many Lhuentse women have looms at home and Khoma is especially famous for its kushuthara (brocade) weaving.

Mongar

Most towns in the west of Bhutan are in valleys. In eastern Bhutan most towns, including Mongar, are on the tops of hills or ridges. A row of large eucalyptus trees protects the town from the wind.

There is little of real interest to see in Mongar, but many people spend a night here before continuing to Trashigang. It takes about 11 hours to drive from Jakar to Trashigang. This often means driving at night, which is a waste in such interesting countryside.

The pleasant main street is lined with traditionally painted wooden Bhutanese buildings decorated with colourful potted plants. Archers sharpen their aim on the football ground most afternoons.

Mongar Dzongkhag

The Mongar district is the northern portion of the ancient region of Khyeng. Shongar Dzong, Mongar’s original dzong, is in ruins, and the new dzong in Mongar town is not as architecturally spectacular as others in the region. Drametse Goemba, in the eastern part of the district, is an important Nyingma monastery, perched high above the valley.

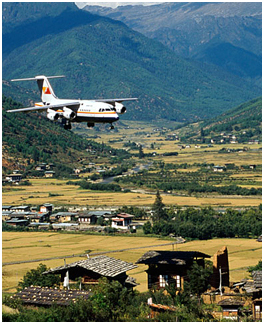

Paro

The charming small town of Paro lies in the centre of the valley on the banks of the Paro (or Pa) Chhu, just a short distance northwest of the imposing Paro Dzong. The main street, built only in 1985, is lined with colourfully painted wooden shop fronts and restaurants, though a modern concrete extension is taking root to the side.

Some of the older shops in Paro have doors at the back; a strange ladder system provides access through the front window. An unusual local regulation has, for a while, prohibited bicycle riding within Paro town.

Paro Dzongkhag With our passage through the bridge, behold a curious transformation. For just as Alice, when she walked through the looking-glass, found herself in a new and whimsical world, so we, when we crossed the Pa-chhu, found ourselves, as though caught up on some magic time machine fitted fantastically with a reverse, flung back across the centuries into the feudalism of a mediaeval age." Earl of Ronaldshay, Lands of the Thunderbolt (1923).

With our passage through the bridge, behold a curious transformation. For just as Alice, when she walked through the looking-glass, found herself in a new and whimsical world, so we, when we crossed the Pa-chhu, found ourselves, as though caught up on some magic time machine fitted fantastically with a reverse, flung back across the centuries into the feudalism of a mediaeval age." Earl of Ronaldshay, Lands of the Thunderbolt (1923).

The Paro valley is without doubt one of the loveliest in Bhutan. Willow trees and apple orchards line many of the roads, whitewashed farmhouses and temples complement the green terraced fields and forested hills rise on either side to create a beautiful, organic and peaceful whole.

The broad valley is also excellent agricultural land and the people of Paro are better off than many elsewhere in Bhutan. One indication of their affluence is the preponderance of metal roofs throughout the valley, which have largely replaced the traditional wooden shingles. Red and white rice, apples, strawberries and asparagus (wonderful in April) all thrive in the fertile soil.

Several treks begin in or near Paro. The Druk Path trek climbs over the eastern valley wall, crossing a 4200m pass before descending to Thimphu. The Jhomolhari, Laya–Gasa and Snowman treks all lead west from Drukgyel Dzong on to Jhomolhari base camp and the spectacular alpine regions of Gasa and Laya beyond.

Phobjikha Valley Phobjikha is a bowl-shaped glacial valley on the western slopes of the Black Mountains, bordering the Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park. Because of the large flock of black-necked cranes that winters here, it is one of the most important wildlife preserves in the country. In addition to the cranes there are also muntjacs (barking deer), wild boars, sambars, Himalayan black bears, leopards and red foxes in the surrounding hills. The Nakey Chhu drains the marshy valley, eventually flowing into the lower reaches of the Punak Tsang Chhu.

Phobjikha is a bowl-shaped glacial valley on the western slopes of the Black Mountains, bordering the Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park. Because of the large flock of black-necked cranes that winters here, it is one of the most important wildlife preserves in the country. In addition to the cranes there are also muntjacs (barking deer), wild boars, sambars, Himalayan black bears, leopards and red foxes in the surrounding hills. The Nakey Chhu drains the marshy valley, eventually flowing into the lower reaches of the Punak Tsang Chhu.

Some people refer to this entire region as Gangte (or Gangtey), after the goemba that sits on a ridge above the valley. The three-day Gangte trek takes off from this valley.

The road from Gangte Goemba winds down to the valley floor and passes extensive russet-coloured fields of potatoes that contrast with the rich green of the valley. Gangte potatoes are the region’s primary cash crop and one of Bhutan’s important exports to India.

The valley is snowbound during the height of winter and many of the valley’s 4500 residents, including the monks, shift to winter residences in Wangdue Phodrang during December and January, just as the cranes move in to take their place. The local residents, known as Gangteps, speak a dialect called Henke. Pockets of the Bon religion reputedly exist in the Taphu Valley.

Phuentsholing

The small, sweltering border town of Phuentsholing sits opposite the much larger Indian bazaar town of Jaigaon, separated only by a flimsy fence and a much-photographed Bhutanese-style entrance gate. Coming from India you will notice an instantaneous change in the degree of cleanliness and organisation. Coming from Bhutan the new air is thick with the smells of the subcontinent. There’s not a great deal to do here but keep cool and soak up the border atmosphere, as Bhutan blurs into India.

Just to the west of town is the wide flood plain of the Torsa Chhu, which in its upper reaches is known as the Amo Chhu and has its headwaters in Tibet’s Chumbi valley. Several hours’ walk away, on the opposite side of the Torsa Chhu, is the home of the Doya minority group.

Royal Manas National Park The 1023-sq-km Royal Manas National Park in south-central Bhutan adjoins the Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park to the north and India’s Manas National Park and Manas Tiger Reserve to the south. Together they form a 5000-sq-km protected area that runs from the plains to the Himalayan peaks.

The 1023-sq-km Royal Manas National Park in south-central Bhutan adjoins the Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park to the north and India’s Manas National Park and Manas Tiger Reserve to the south. Together they form a 5000-sq-km protected area that runs from the plains to the Himalayan peaks.

The area has been protected as a wildlife sanctuary since 1966 and was upgraded to a national park in 1988. It is the home of rhinos, buffalos, tigers, leopards, gaurs, bears, elephants and several species of deer. It is also home to several rare species, including the golden langur, the capped langur and the hispid hare. The 362 species of birds in the park include four varieties of hornbills. Unfortunately, because of security concerns related to separatist groups in India, at the time of research it was not possible to visit Manas.

Samdrup Jongkhar

There’s little reason to linger in this sweltering border town. The streets are jammed with Tata trucks and every morning and afternoon a tide of Indian workers crosses the border to work in the town. A Bhutanese-style gate decorated with a dragon and garuda bids you farewell as you cross into the heat and chaos of India.

Electricity is rather haphazard in Samdrup Jongkhar.

Sarpang Dzongkhag

Sarpang is on the southern border and a large part of the district is protected within the Royal Manas National Park. Kalikhola in the far west is a border town that has no road connection with the rest of Bhutan; all travel here involves passing through Indian territory. There is talk of building an airport in Gelephu.

Southern Dzongkhags

This dzongkhag is generally closed to tourists.

This district (previously spelt ‘Chirang’) is in the south of the country, but is separated from the southern border by Sarpang Dzongkhag.

The major town is Damphu, reached by a road leading south from Wangdue Phodrang. The road passes through Sankosh, said to be the hottest place in the country, then continues southeast from Damphu to the border town of Sarpang.

Thimphu You approach Thimphu along a winding, single-lane access road, little wider than the trucks that suddenly emerge around each curve. Each blind bend promises a glimpse of your destination; however, for most of the journey all that is revealed is another curve followed by another. The steep hillsides are dotted with houses, some abandoned, their massive earthen walls slowly crumbling, and the occasional white-washed temple. Suddenly the road drops to a modern expressway on the valley floor, whisking you through paddy fields to the capital of one of the world’s most intriguing countries.

You approach Thimphu along a winding, single-lane access road, little wider than the trucks that suddenly emerge around each curve. Each blind bend promises a glimpse of your destination; however, for most of the journey all that is revealed is another curve followed by another. The steep hillsides are dotted with houses, some abandoned, their massive earthen walls slowly crumbling, and the occasional white-washed temple. Suddenly the road drops to a modern expressway on the valley floor, whisking you through paddy fields to the capital of one of the world’s most intriguing countries.

Established as the capital in 1961, Thimphu has a youthful exuberance that constantly challenges the country’s conservatism and proud tradition. The ever-present juxtaposition of old and new is just one of its appealing qualities. Crimson-robed monks, Indian labourers, gho- and kira-clad professionals and camera-wielding tourists all ply the pot-holed pavements, skirt packs of sleeping dogs, and spin the prayer wheels of Clocktower Square, and nobody, it seems, is in a hurry. Thimphu is the world’s only capital without traffic lights. A set was installed, but the residents complained that it was impersonal, and so gesticulating, white-gloved police continue to direct the ever-increasing traffic. As well as being a classic Bhutanese anachronism, it may well be the city’s most photographed spectacle.

Thimphu offers the best opportunity to do your own thing. It’s relaxed, friendly and pretty informal, and is most rewarding if you can be the same.

Trashi Yangtse

The new settlement of Trashi Yangtse is near the Chorten Kora, 3km from the old dzong. The new dzong and rapidly growing town occupies a large bowl in one of the furthest corners of the kingdom, 550km from Thimphu. The dzong was inaugurated in 1997 and, being new, has little historical or architectural significance.

The town is known for the excellent wooden cups and bowls made here from avocado and maple wood using water-driven and treadle lathes. Trashi Yangtse is also a centre of paper making. They use the tsasho technique with a bamboo frame, which produces a distinctive pattern on the paper.

Trashi Yangtse Dzongkhag

Previously a drungkhag (subdistrict) of Trashigang, Trashi Yangtse became a fully fledged dzongkhag in 1993. It borders the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, and there is some cross-border trade. The old trade route between east and west Bhutan used to go through Trashi Yangtse, over the mountains to Lhuentse and then over Rodang La (4200m) to Bumthang. This difficult route fell into disuse when the road from Trashigang to Bumthang via Mongar was completed. The district lies at the headwaters of the Kulong Chhu, and was earlier known as Kulong.

Trashigang

Trashigang is one of Bhutan’s more interesting towns and a good base for excursions to Trashi Yangtse, Khaling, Radi, Phongme and elsewhere in eastern Bhutan.

Accommodation here is fairly limited, but there is a variety of restaurants and you’re bound to find at least one amusing place to drink among the town’s 21 bars. Not many tourists make it to Trashigang, but there used to be many Canadian teachers working here and the people of Trashigang are used to Westerners.

Villagers come to town on holy days, which occur on the first, 10th and 15th of the Bhutanese month, to trade and sample the local arra.

Trashigang Dzongkhag

Trashigang is the heart of eastern Bhutan and was once the centre of important trade with Tibet. There are several goembas and villages that make a visit worthwhile, but a lot of driving is required to reach this remote region.

Wangdue Phodrang Dzongkhag

The scenic dzongkhag of Wangdue Phodrang is centred on the town and dzong of that name and stretches all the way to the Pele La and Phobjikha valley.

Western Bhutan Whether you arrive by air at Paro or by road at Phuentsholing, your first impression of Bhutan is one of stepping into a world that you thought existed only in storybooks or your imagination. Vertical prayer flags flutter in the breeze and men dressed in a traditional gho (tunic) and Argyle socks stroll past yellow-roofed shrines and wooden slate-roofed houses. It soon becomes clear that you are well off the beaten path of mass tourism.

Whether you arrive by air at Paro or by road at Phuentsholing, your first impression of Bhutan is one of stepping into a world that you thought existed only in storybooks or your imagination. Vertical prayer flags flutter in the breeze and men dressed in a traditional gho (tunic) and Argyle socks stroll past yellow-roofed shrines and wooden slate-roofed houses. It soon becomes clear that you are well off the beaten path of mass tourism.

As with the rest of country, western Bhutan is a collection of valleys. The remote Haa valley in the far west is separated from the Paro valley by the 3810m Cheli La. The relatively built-up Thimphu valley to the east is divided from the historical centres of Punakha and Wangdue Phodrang by the 3140m Dochu La. East of here the rugged Black Mountain range forms an even greater barrier that separates western Bhutan from the rest of the country. North of here, the upper valleys are trekking territory, leading to the sacred peak of Jhomolhari, the Tibetan border and the fascinating and remote regions of Laya and Gasa. To the south are the lush foothills and the all-important road to the Indian border at Phuentsholing.

This is the region of Bhutan that most tourists see and for good reason. It’s the heartland of the Drukpa people, home to the only airport, the capital and the largest, oldest and most spectacular dzongs in the kingdom. Whether it’s the beginning of your trip or the all of your trip, it’s a spectacular introduction to a magical land.